The Glorious Permian

Glorieta Mesa with the Santa Fe Range beyond

Glorieta Mesa

Visitors driving east from Santa Fe along Interstate 25, on their way to Pecos National Historical Park, or Las Vegas, NM, or Denver, CO, are soon greeted by an impressive and colorful escarpment of layered rock on the south side of the freeway. This long, flat-topped landform is called Glorieta Mesa. The beds we see in the cliffs once covered all of this region, but as the older and stronger rocks upon which they rest were pushed up during the birth of the Rocky Mountains, north of here, the colorful beds were stripped away by erosion. Today the stronger rocks stand as the peaks and ridges of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The curve of the interstate highway, the rail line of the Santa Fe Chief, and even the obscured track of the Old Santa Fe Trail make their way along the contact between the durable rocks to the north, and the gently tilted escarpment to the south - a contact which opened a human passageway around the formidable barrier of the southern Rocky Mountains.

Pangaea

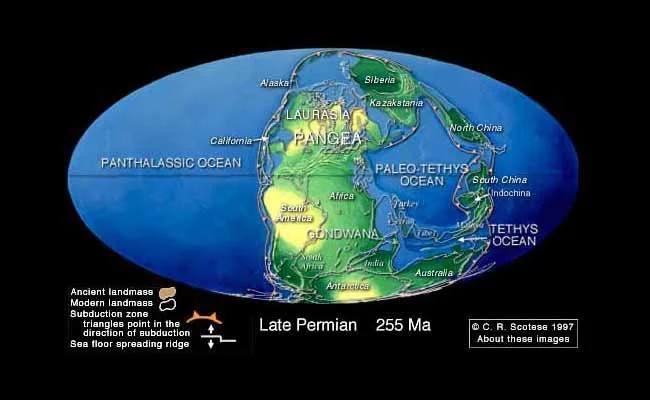

The warmly-colored rocks we see beneath the scattering of juniper and pine were all laid down as sediments during the Permian Period of our planet’s long history, around 290 to 270 million years ago. This was the time of Pangaea, when all of Earth’s continents were gathered into one landmass. Much of this supercontinent lay south of the equator, near the South Pole. New Mexico lay just a few degrees north of the equator. Such an arrangement of 'all Earth’ and ‘all Sea’ - Panthalassa - led to climatic conditions very different than the ones we experience today. Much of Pangaea was arid, or subjected to strongly seasonal rainy periods like the monsoons of modern India.

Pangaea in Late Permian time

Red beds

The Permian is famous for its “red beds”. Red beds are sedimentary rocks consolidated from sand and mud deposited in continental rather than marine settings. If these settings are arid or seasonally arid, the sediments will be exposed to the oxygen in the air as they consolidate. This exposure basically rusts the iron in the mineral “glues” that turn sediment into rock, yielding a variety of warm colors that range from yellows through oranges and reds, to nearly purple. The rocks in Glorieta Mesa are classic Permian red beds.

The Permian Basin

The Permian Period has special significance to those of us here in New Mexico. Where the colorful continental sandstones and mudstones dive into the subsurface to our south and east, thick layers of limestone appear above them. Limestones are consolidated from the chalky muds of calcium carbonate that form in shallow, warm marine environments. They are rather drab rocks, but they let us know that an arm of the ocean was lurking south of the shifting red desert sands. This isolated embayment of the sea, located in southeastern New Mexico and adjacent West Texas, is now called the Permian Basin.

Permian Reefs

Large barrier reefs formed around the perimeter of this basin. These reefs divided shallow lagoons from deeper waters, rich in nutrients, and they teemed with biological activity. The limy skeletons of marine organism piled into great banks of calcium carbonate just beyond the waters of the turquoise lagoons.. During shifts in sea levels, these reefs would be abandoned, only to reform again, and the steady slow sinking of the basin floor buried each one in turn, like the stacked ruins of an ancient city. If you want to visit one of these ruins, head down to Carlsbad Caverns National Park, and take a subterranean journey into the heart of a Permian reef, hollowed out by groundwater and acidic vapors.

On the edge of the Permian Sea in New Mexico

Oil!

The increasing aridity of Pangaea doomed the beautiful reefs, but it ensured the future wealth of New Mexico and Texas. As the sea covering the Permian Basin dried up and died, around 250 million years ago, thick beds of rock salt and gypsum draped themselves over the limestones like a dead white shroud. The stage was set for the birth of one the worlds greatest oil provinces: a rich source of organic matter buried at just the right depth to cook into petroleum, a thick and utterly impervious seal of salt above (so effective that we isolate radioactive waste in the salt mines of Carlsbad), and plenty of porous zones in the limestone banks and sandstone bars to capture and store the black gold for future prospectors to find. Nature hid this bounty well; prior to 1921, one hundred years ago, the Permian Basin was derided as the '“petroleum graveyard of Texas”. But by 1980 it was producing 20% of the United State’s ravenous appetite for oil, and with the new technology of horizontal drilling, continues to be the gift that keeps on giving.

About the author

Scott Renbarger is a local outdoor enthusiast and guide in Santa Fe, and occasional adjunct instructor of geology at Santa Fe Community College. He is a board member of the Santa Fe Professional Tour Guides. Through his company Outspire Hiking and Snowshoeing, Scott leads individually-arranged hikes for small groups in Santa Fe National Forest, Bandelier National Monument, and the canyon country along the Rio Grande. Snowshoe adventures are offered in the winter season when conditions permit. And he’s always happy to set up a geology walk - his favorite subject! - for you, in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains above Santa Fe.